Italian Immigrant Experience

Italian immigrants1 moved from their old country in order to embrace a new way of life in their adopted nation. They pinned their hopes on the name of a land, the United States of America. Henceforth, their descendants would consider themselves Americans, or in remembering their heritage, Italian Americans. But their new neighbors often still labeled them as Italians, and therefore different from real Americans.

In the period from the 1880s to the 1920s, Americans saw the arrival of 4 million Italian immigrants to the United States. The majority of this influx came from depressed or impoverished regions in southern Italy, rather than from the more prosperous north.

In general, these new arrivals were not welcomed with the helping hand nor easy acceptance that one might expect from a democratic nation founded by other, earlier immigrants. Instead, Italians often faced prejudice and mistrust, which sometimes escalated to violence. They had to struggle for fair treatment and respect, as they encountered ignorance, lack of understanding, competitiveness, and xenophobia. In short, they contended with harsh conditions that had many facets – if it had occurred a century later it would be called “discrimination” and “racism”.

To the American public at large, those arriving from Italy tended to be ostracized as the alien “Other,” both feared and looked down upon. For economic reasons, many Italians congregated in urban neighborhoods, which then came to be viewed as unsafe enclaves by the public at large.

The jobs that the Italian immigrants took were often for low wages and dangerous. For example, many Italians initially arrived in northeastern Pennsylvania to work in the coal mines and textile mills, and on the railroads. They were subjected to unsafe working conditions, low pay, and long hours. The Italian Immigrant experience is also explained in an article by Kathleen Brush in the "Latest News" section of this website.

The Crescent City Hangings and Columbus Day

During the period of heavy immigration by Italians, white Anglo Saxon Protestants (WASPS) dominated the country’s established power positions and were generally not tolerant toward Catholics, which, of course was the principal religion of Italians.

Standing out as perhaps the most extreme expression of anti-Italian sentiment—The Crescent City Hangings, as they are often called—were considered to be the largest mass lynching in American history. It is an incident that seems to be omitted from the normal study of American history, perhaps because it was such an embarrassment to our nation. So, very few Americans have ever heard of it.

The lynching of 11 Italians took place in New Orleans, Louisiana on March 14, 1891. Nineteen men, all Italians, were indicted the previous November for the murder of New Orleans’ Superintendent and Chief of Police, Dave Hennessy. It was after the verdict of not guilty was announced for these first 11 men that an attack on the prison took place. When the violence was over, ten of the men were dead and one was critically injured.

Ultimately, President Benjamin Harrison ordered a U.S. government payment of $25,000 to the families of the Italian citizens who were victims of the lynchings. In 1892 he also established a holiday which he named “Columbus Day” to show some respect for Italian immigrants and their contributions to America. He chose the name not to honor Columbus, but because coincidentally it was the 400th anniversary of the arrival of Columbus in America in 1492. In 2019 the mayor of New Orleans officially apologized to the Italian community for the lynchings.

Continuing Discrimination

Sadly, even after the lynchings, whatever the reasons for the ongoing intolerance and prejudice, virulent stereotypes cast Italians—especially Sicilians and immigrants from the southern Italian regions—as criminals, beggars, and lazy ne’er-do-wells. These damaging views proliferated throughout the entire United States, spread in conversations by ignorance and small-mindedness and seemingly endorsed as true by the mainstream media.

With no regard for repercussions on the Italian immigrants, the media propagated a negative perception of Italians by printing sensationalized stories designed to sell newspapers. For example, in 1893 the New York Times hyped the deportation from Ellis Island of nine Italian immigrants who had been jailed for petty crimes, referring to Italians as bandits, bravos, and cutthroats, engaged in vendettas and feuds.2

Newspapers and magazines consistently chose words and covered stories that highlighted only the negative and, in many instances, ignored reality completely.3 Unfortunately, the Italian Americans had little recourse against this fear-mongering. They were not sufficiently organized or cohesive as an ethnic group to launch a concerted reply, and any response only seemed to reinforce the views of their detractors.

Italian Americans as Enemy Aliens and Inferior Genetics

After World War I ended in 1918, Italian Americans were divided further by the general American population by the rise of the Fascist party in Italy. This occurred even though the Italians had been American allies during World War I.

Another example of continuing anti-Italian prejudice was the change in U.S. immigration laws in 1921. The discovery of eugenics in the late 19th and early 20th century provided a “scientific” basis to cut off Italian immigrants. An anti-immigration movement, led by Boston Brahmins, contended that biology had validated the genetic inferiority of Italians, Jewish people, and other southern and easter Europeans. The result was an immigration law, known as the Immigration Restriction Act of 1921, passed by our U.S. Congress that virtually ended legal immigration by Italians. The law stayed in place for over 40 years until it was changed in 1965.

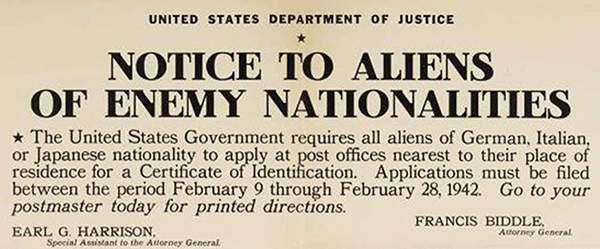

In addition, by 1940, as the U.S. edged closer to war, more than 600,000 Italian immigrants were labeled as “enemy aliens” or “resident aliens.”4 Some Italians were immediately deported, approximately 1,500 Italian Americans were arrested by 1942, and approximately 250 Italian Americans were suspected of being saboteurs or were otherwise considered dangerous—often on little or no evidence—and were interned in military camps around the country. During this period, the U.S. government took similar actions against U.S. Citizens from Germany and Japan. This occurred despite the fact that the vast majority of Italian Americans and most Italians rejected Benito Mussolini’s regime (1922–1943) by the time the United States entered World War II in December of 1941.

Law-abiding Italian Americans were understandably angry and unhappy to be labeled as enemy aliens, especially as more than 500,000 Americans with Italian backgrounds were fighting in the war on the side of the Allies. Many others were working in U.S. factories, part of the massive industrial effort that was essential to military success and had volunteered in various World War associations, like the Red Cross Nursing Reserve.

There were vigorous petitions made to the U.S. government to have the “enemy alien” designation removed. Trade union representatives launched a protest, for example, on behalf of their 200,000 Italian American members who had started citizen paperwork before the United States entered the war. Like many of German and Japanese descent, Italian Americans did not feel it was fair to be stigmatized and treated with suspicion just for their ethnic heritage. In October 1942, restrictions were eased.

Rising Italian American Contributions

Concurrently, some notable Italian Americans rose to prominence, helping to change views. These included the war hero John Basilone, physicist Enrico Fermi (who created nuclear energy), and factory worker Rose Bonavita (known as Rosie the Riveter). And gradually Italian Americans began to be portrayed as “innocent but patriotic Americans who eagerly learned American ways.”5

The portrayals of Italian Americans in the popular culture of the United States make clear a timeline of common perceptions, good and bad, of the ethnic group. Professors Luciano J. Iorizzo and Salvatore Mondello studied Italian American stereotypes in mainstream American culture up to the year 1980. They generalized that on the positive side, Americans were attracted to the artistic side of Italians in the nineteenth century, for example, Enrico Caruso was a highly acclaimed Italian operatic tenor of the early 1900’s, regularly singing at opera houses across the United States including the Metropolitan Opera.

Italian Americans Stereotypes - Gangsters, Lovers, etc.

Sadly, over the same 20th century period, Italians were regularly accused of participating in organized crime syndicates, such as the Mafia, by having far-flung connections, or being accused of passively paying to be left alone by those groups. For example, Al Capone, born in America to Italian immigrants, rose to fame and notoriety during the Prohibition era (1920 – 1933) as the head of a criminal bootlegging syndicate. Fear of—and fascination with—this underground world led many people to believe that all Americans of Italian descent had illicit connections with organized crime.

Of course, the stereotypes of Italian Americans as lawless and violent are false. In the first thirty years of the twentieth century, immigrants (including Italians) were less likely than the American-born individuals to be incarcerated. And, as of 2012, the Italian American population consisted of about 17.3 million individuals, but only slightly fewer than 3,000 are thought to be involved in organized crime of any kind.6

Italian Americans also became the butt of jokes and seen as “comical, always good for a laugh.” The 1920s characterized them as racketeers and lovers, two of the five stereotypes (along with artists, showmen, and family men) that were prevalent in the 1930s. In the World War II era, Italian Americans became known for their heroes and icons, for example, Joe DiMaggio became a towering sports star and Frank Sinatra a giant in the music and entertainment worlds.7

Around the mid-20th century, Italian American women were not treated or viewed kindly, and the Italian American family structure was not seen as the ideal. Going into the 1960s, the Italian American was still caricatured as a “lower-middle-class clod” and worse, as “a hard-hat racist.” Finally, in the 1970s the reputation of the Italian American seemed to improve, to the point where this ethnicity became “chic” and “represented by the media as typical Americans rather than stereotyped Italian Americans.8

But negativity did not completely disappear. The Italic Institute of America (IIA) found that between 1972 and 2002, there were 293 “mob movies.” showing negative Italian American stereotypes.9 Throughout the last thirty years, television programs in particular have shown Italian American characters as sweet but stupid ladies’ men or as loud, temperamental women. Movies such as The Godfather and the Sopranos television series only helped to propagate these myths. Italian American groups and individuals are challenging these stereotypical representations and pushing for more accurate, well-rounded characters.

In 2001, Camille Paglia, the daughter of an Italian immigrant, joined the fight against The Sopranos and reportedly stated, “Real Italian-Americans finally got noticed after the World Trade Center attack in 2001, she said. The people who have been the invisible “backbone” of our nation’s infrastructure—the police, firefighters, and janitors—were being recognized as the sexy heroes they deserved to be.”10

Italian Americans Meld into America

In the decades since World War II, Italian Americans have seen negative perceptions slowly dissolve. Despite the movies and TV characterizations, most people now recognize the stereotypes of Italian Americans as second-class citizens, or as members of the mob, or as loud and temperamental, as exaggerations which have precipitated a decline in these characterizations in today’s culture.

Despite the discrimination, Italian immigrants living in the United States gradually became Americans, adopting American values, and, with time, taking official steps towards citizenship. After all, in the words of political columnist Charles Krauthammer, “America’s genius has always been assimilation, taking immigrants and turning them into Americans.”11 This idea can be traced all the way back to the beginnings of the country, when George Washington wrote to John Adams, “Whereas by an intermixture with our people, they, or their descendants, get assimilated to our customs, measures and laws: in a word soon become one people.”12

This fundamental principle of the founders carried over to Italian immigrants. The succeeding generations of Italian Americans, although fully grateful and respectful of the sacrifices of their ancestors, are indeed true Americans.

1 The majority of this text was written by American Ancestors | NEHGS

2 Cannato, American Passage, 93.

3 “Those Who Followed Columbus,” 128-129, citing Jacob Riis, How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1890). [The 1893 deportation made all southern Italians out to be criminals, when in actuality Italy had its own laws preventing anyone with a criminal record from emigrating. The reputation of the Italians as beggars was perpetuated despite Jacob Riis’s finding that only 2 percent of the vagrants arrested in New York City circa 1889 were Italians.]

4 As “enemy aliens,” they were required to register at post offices, be fingerprinted and photographed, and carry special ID cards. They lost the rights to travel freely and to carry cameras and guns. Many Italian Americans were forced to move their homes and businesses, if it was determined that they were located too near factories, shipyards, and power plants.

5 Joan Saverino, “Rural Roads, City Streets: Italians in Pennsylvania,” website of Historical Society of Pennsylvania, online at https://hsp.org/education/unit-plans/italian-immigrants-in-pennsylvania/rural-roads-city-streets-italians-in-pennsylvania; Iorizzo and Mondello, Italian Americans, 248-262, 276.

6 Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), “Italian Organized Crime,” online at https://www.fbi.gov/investigate/organized-crime; “American Community Survey,” on the website of the U.S. Census Bureau, at https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs.

7 Iorizzo and Mondello, Italian Americans.

8 Iorizzo and Mondello, Italian Americans, 265-284.

9 Italic Institute of America (IIA), “Image Research Project: Italian Culture on Film (1928-2002),” online at https://italic.org/.

10 Libby Rosof, “Tony Soprano takes a hit from Camille Paglia,” Penn Current, 29 Nov. 2001, online at https://penntoday.upenn.edu/2001-11-29/latest-news/tony-soprano-takes-hit-camille-paglia.

11 Charles Krauthammer, "Assimilation Nation," Washington Post, 17 June 2005.

12 George Washington to John Adams, 15 November 1794, The Writings of George Washington, edited by John C. Fitzpatrick (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1931-40), Vol. 34 p. 23.